Professor Leslie Wilkinson, OBE

Professor Leslie Wilkinson OBE

1882 - 1973

Architect and academic

Professor Leslie Wilkinson, OBE made an exceptional contribution to the field of architecture in Australia as a gifted and innovative practitioner, an educational leader and an advocate for his profession. He left behind a tangible legacy in the buildings that survive him, while the influence he brought to bear on local architectural practice and thinking was profound.

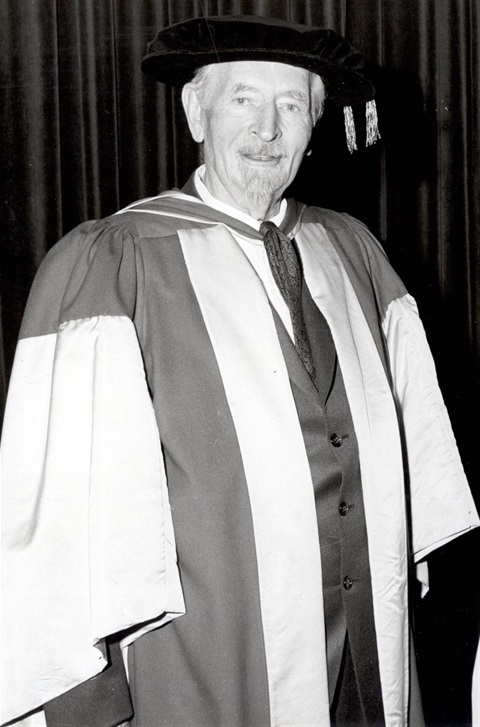

Image: Emeritus Professor Leslie Wilkinson photographed in 1970 G3_224_1081. Image Courtesy of the University of Sydney, Archives.

Plaque location

24 Wentworth Road Vaucluse

View all plaques in Woollahra

Plaque Unveiling Gallery

Speech - Plaque Unveiling - Prof Andrew Leach(PDF, 53KB)

Speech - Plaque Unveiling - Cr Mary Lou Jarvis(PDF, 245KB)

Family life

Australia’s first Professor of Architecture, Leslie Wilkinson, was born on 12 October 1882 in New Southgate – today a suburb of the outer boroughs of London, but in 1882 a locality within the newly established district of New Southgate.

Leslie was the son of Edward Henry Wilkinson (known as ‘Harry’) and his wife Ellen, née Barker. Harry Wilkinson gave his occupation as 'gentleman' when Leslie was baptised on 16 December 1882 at St Paul’s Enfield, in the Parish of New Southgate, County Middlesex.[1] He would do so again, almost thirty years later in 1912, in the register recording Leslie's marriage.[2] Elsewhere however, Harry’s occupation has been described as a commercial clerk,[3] and by the account of Leslie’s grandson, David Wilkinson, Harry’s employer was the Nelson Dale Gelatine Company, from which he retired early. David would note that this withdrawal from salaried work was to the detriment of family finances, giving his grandfather Leslie ‘habits of thrift which would last him all his life.[4]

Harry and Ellen's family consisted of four children. Leslie’s siblings were an older sister and brother, Theodora Kathleen and Harrie Vaughan (known by his second name) who had been born in 1880 and 1881 respectively, and a younger sister, Ella Madeleine, whose mid-1884 birth followed Leslie’s by a little under two years.[5] During Leslie’s childhood, the family moved house as dictated by financial circumstances, but remained within the New Southgate district. Here, the context of Leslie’s childhood and youth was that of a ‘typical middle-class Victorian household’, in the words of David Wilkinson – its most memorable disruption being a prolonged period of ill health in his late teenage years.[6]

While the adult Leslie Wilkinson ranked this convalescence as his ‘dark period’, and his illness culminated in a poor health prognosis, the gloomy prophesy was not to be fulfilled. Wilkinson recovered, lived to be over ninety, and was still physically active in his architectural practice in his late eighties. As for his time spent bedridden as a youth, it was used for reading and sketching, a resourceful way for this future architect and academic to prepare for the life that lay ahead.

St Stephen’s, Ealing c1890.

In 1912 Leslie and Dorothy Wilkinson were married at this church, where their first two children, Bridget and George, were also baptised. Shown here in 1890

with the steeple under construction. Image source unknown.

The next chapter of Leslie Wilkinson’s family life began with his marriage to Dorothy – the beginning of a thirty-five year union. On 11th April 1912 at St Stephen’s church West Ealing, the 29-year old Leslie Wilkinson, his profession described as 'architect', married 27-year old Alice Dorothy Ruston, the daughter of Frederick Ruston, a stockbroker.[7]

Dorothy and Leslie would have three children. Their first were wartime babies, and Londoners by birth: Gwendoline Bridget (known as Bridget) born 12 July 1914 [8] and George Leslie Ruston, born 25 August 1917.[9] The third of the Wilkinson children, a second daughter, Elizabeth Mary, was born in Sydney on 6 th November 1922, at the family’s newly built house, Greenway.[10] Elizabeth would be the only one of Wilkinson’s children to follow him into the career that was his own passion. One of only four women in her year to graduate in architecture from Sydney, Elizabeth was awarded the Sir John Sulman prize for design when her degree was conferred in June 1947.[11]

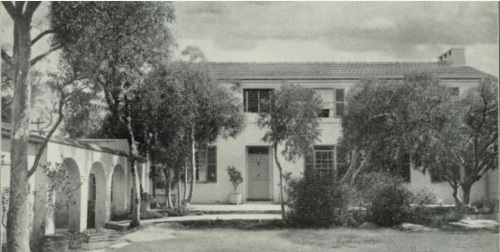

The Wilkinson family was close-knit. The house that Leslie Wilkinson would build in Vaucluse, and which would be his home for over fifty years, was the hub of family life following the move occasioned by Leslie’s 1918 appointment to the University of Sydney. Greenway, at No 24 Wentworth Road, was a living example of what Wilkinson would express in a short article written four years before the house was built:

“But a house is not an end in itself; our houses and gardens should not seem complete in themselves but should modestly invite the human complement – mine host, his family and friends.

Domestic architecture in Australia… Syd., Angus & Robertson 1919 p. 3

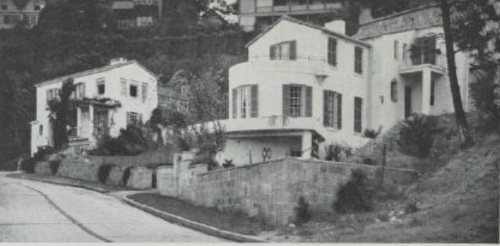

Entrance to Greenway,corner of Fisher Avenue and Wentworth Road

Photographed 2024.

Following other of his principles, Wilkinson put great thought into not only the design of the family home, but its placement on the site and, ahead of that, the choice of its broader setting. Diary entries tell of him covering miles on foot in his early exploration of the city where his career had brought him. On 21 September 1918, a little over a month after his arrival, he walked from Botany Bay to South Head, ‘to acquaint himself with Sydney.[12]

Most of his university colleagues lived ‘along the western line,’ but early in 1919, Wilkinson headed east, renting a flat in Darling Point to prepare for his family’s February arrival. The following month he took Dorothy, Bridget and George to Vaucluse, to view the locality which he hoped would be part of their collective future.[13] That hope was translated into reality with a purchase of land in late 1921,[14] and the construction of Greenwayin 1922.

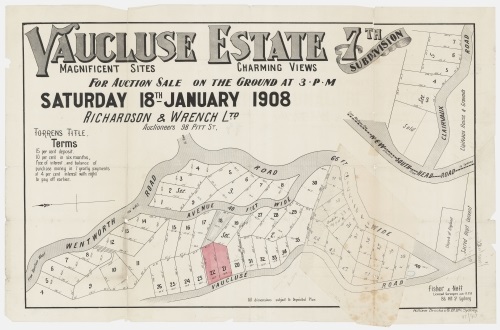

Subdivision plan of the 1908 release of the 7 th subdivision of the Vaucluse estate.

SLNSW - 081 - Z SP V1 80a - FL9124015

Leslie Wilkinson purchased the vacant corner allotment – Lot 14, Section 2, measuring 36¾ perches - from an earlier buyer.

The Vaucluse house would become an intergenerational home in Leslie Wilkinson’s later life. After the death of Dorothy in 1947,[15] Leslie Wilkinson’s eldest daughter Bridget ‘kept house’ for him and became ‘his companion for the rest of his life,[16] and from the late 1940s until 1958, his son George and daughter-in-law Coral and their family were also part of the household at Wentworth Road.[17] George had met Coral Edith Clabburn through their joint WWII RAAF service, and the couple had married in Melbourne in 1946.[18] They would have five children, all of whom called Greenwayhome at various stages.

Unsurprisingly, an architectural solution was applied at 24 Wentworth Road to ensure these post-war family circumstances were thoughtfully managed,[19] in line with Wilkinson’s assertion that ‘convenience in planning and arrangement’ is one of the three most important qualities of ‘good architecture of any age’.[20] The ‘tower’ addition to Greenway received approval from Woollahra Council in 1950.[21]

The ‘tower’ addition at Greenway, on the Fisher Avenue frontage. Photographed 2024.

In 1958, when George and Coral moved from Greenway,they did not remove themselves far from the family circle. They purchased a house in Greycliffe Avenue, at the opposite end of the same suburb,[22] and they would later return to 24 Wentworth Roadand again make it home. Bridget and George jointly inherited their father’s house, [23] but following his death, Bridget relocated to the Southern Highlands – another of the family’s favourite regions, where holidays where spent from soon after their arrival in Australia.[24] Greenwaywas transferred to George and Coral Wilkinson, [25] and remained in family hands for many years after the death of its builder.

While Greenway was the family anchorage, Wilkinson also swept his young family away on lengthy excursions abroad, part of his firm belief in the necessity of travel to an architect’s vocation, its pleasures and learnings shared whenever possible with his wife and children. In 1926, he took study-leave from the University of Sydney and the family spent nine months touring England, Greece, Italy, France, and Scandinavia while the Professor studied the architecture of the places they visited.[26] Wilkinson’s reports on return to Sydney, on matters ranging from social housing provision in the U.K. to the merit he saw in Swedish design, found a place in the mainstream press [27] as much as it was a subject of discussion among peers.[28] This would have pleased him. In line with the University’s philosophy, he believed his academic life existed as much to serve the community at large as to serve his students and the institution itself.

Eight years later, an article published in the social pages of The Home records a farewell party given by the president of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) for Leslie, Dorothy and their daughters as they set sail for England on the Orsova,bound for ‘a long holiday.’ [29] George Wilkinson was already settled in England by the time his family departed Sydney in December 1934, having earlier that year sat his preliminary law examination, as a sixteen-year-old.[30] The trip offered Leslie and Dorothy a family reunion with their son, as well as cultural and educational opportunities for Leslie and the family as a whole.

Wilkinson’s appetite for family travels did not wane with age. When his youngest daughter Elizabeth embarked on her own post-graduation travels shortly after the death of her mother, he joined her for the last part of her eighteen months abroad. The first part she had dedicated to working on staff at Middlesex Council designing school buildings, but the second was set apart for touring with her father. The two covered England, France, Italy and Switzerland together, Elizabeth studying the architecture of the regions while her father attended housing, town planning and architectural conferences in Zurich and Lausanne, and studied housing schemes being carried out in England.[31]

On the last leg of their travels, the sea voyage home to Sydney, Elizabeth met her future husband, Peter Hare.[32] The son of Canon F M Christian Hare of Stowe-on-the-Wold Gloucestershire, Peter was on route to a new position at Geelong Grammar following a period as History master at Sandhurst. The couple married in Vaucluse in August 1949.[33]

Leslie and Dorothy Wilkinson had always intended to settle in Europe when his time at the University of Sydney was over, [34] but Dorothy’s death, coming just before his retirement, removed the pleasure of this plan, and Leslie remained in Sydney. Throughout his decades in Australia, Leslie had retained regular contact with his family in England. His brother Vaughan, who had spent much of his life in Shanghai and Hong Kong for his work, would visit Leslie in Sydney after his own retirement.[35] But Leslie would ultimately outlive all three of his siblings.

Family life in its last stages was inevitably centred on those nearby, his final years enriched also by the many friends he had accumulated over his years in Sydney. Leslie Wilkinson died at Greenwayon 20 September 1973 ‘following a day when he was as alert as ever, having played chess (a lifelong enthusiasm) in the afternoon, and spent the evening in the company of his family, talking and reading.’ [36]

Studies

Leslie Wilkinson’s education began with a tutor amid a handful of boys of his neighbourhood, followed by several years of boarding at St Edward’s School, Oxford, which he attended along with his older brother Vaughan. Reserved for the sons of clergy, the school nevertheless admitted the two Wilkinson brothers - a concession believed to have been based on their claim to two uncles who were Anglican men of the cloth, this outweighing the fact that their father was not. Family lore also has it that both brothers heartily disliked the experience of their years at ‘Teddies’, which for Leslie culminated in his illness.[37]

Schooling and ill health behind him, Leslie Wilkinson qualified as an architect via the time-honoured system of pupillage. First came an apprenticeship to Charles Eamer Kempe, a celebrated stained glass designer, after which he was articled to a prominent London-based architect James Glen Sivewright Gibson, FRIBA. This second arrangement came about through the influence of a family friend and neighbour, a Mr Brown, who recognised Wilkinson’s artistic gifts and believed they had broader potential.[38] From his apprenticeship to Kempe, Wilkinson absorbed an appreciation for traditional decoration and motifs that would later flower in the detail of his architectural work. Gibson’s guidance and instruction, however, would allow him to emerge as a fully-fledged architect.

Articled to Gibson in 1900 for three years, Wilkinson now had not only an opening into the field of architecture, but the opportunity to observe first-hand the management of medium to larger-scale commercial and public projects, due to Gibson’s standing in London and the work his firm attracted. He also launched himself into his associated studies, enrolling in drawing classes at the Hornsey School of Art and technical training at the Northern Polytechnic College, London.

In 1902, Wilkinson enrolled in architectural studies at the Royal Academy London, and in the following year passed the Intermediate examination of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). In 1907, he would pass the final RIBA examinations, having qualified in 1905 for extension to the full five years of study at the Royal Academy. He was also elected in 1907 as an associate of RIBA.[39]

View of Burlington House, London,

home of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Reproduced in the Illustrated London News 1873.

The years between joining the Royal Academy and achieving final qualifications, and those immediately subsequent to that milestone, were astonishingly productive and rewarding, both within the office - where Wilkinson became Gibson’s assistant in 1903, and worked on competitions and major undertakings of the firm – and in his studies, where he won numerous prizes:

1903:

- Royal Academy silver medal – measured drawings

1904:

- Royal Academy £10 premium for Design;

- Royal Academy Silver medal for perspective;

- Royal Academy Travelling studentship for study in England;

- Royal Academy Book Prize

1905:

- Royal Academy £25 premium for Design;

- Royal Academy Gold medal for drawing

- Royal Academy Travelling studentship for study abroad;

- Royal Academy Book Prize

1908:

- RIBA medal for measured drawings

1909:

- Arthur Cates Prize, RIBA Final examinations – measured architectural drawings

Now a qualified and recognised professional in his field, whose Royal Academy results rightly dazzled, Leslie Wilkinson’s attainments nevertheless did not include a university degree. It was then fifteen years since the University of Liverpool, in 1894, had introduced the first course leading to a degree recognised by RIBA, [40] so this qualification would have been chronologically within his grasp. Whether he ever considered study at Liverpool appears not to have been documented. It is plausible, however, that the prospect of training under the auspices of a well-credentialled London practitioner, supported by courses available at respected London-based institutions, seemed as sound an option as any to the young Leslie Wilkinson. Despite the lack of a Bachelor degree, he was destined for a life of university academia.

On 2 May 1970, almost seventy years after qualifying to practice, sixty years after his appointment as a junior academic at the University of London, [41] and fifty after his appointment as the Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at Sydney, [42] the 87-year old Emeritus Professor Leslie Wilkinson collected his first university degree. The award, an honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of Sydney, also marked the highest academic accolade that this institution could offer him.

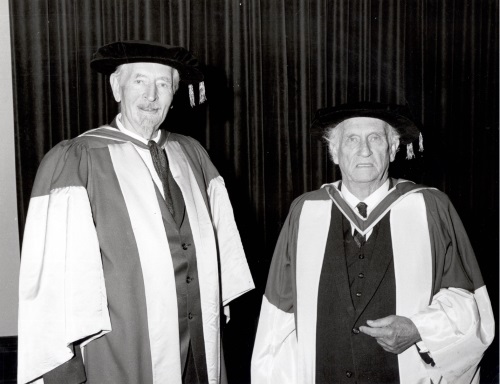

Emeritus Professor Leslie Wilkinson (left) wearing the robes of the D Litt.Photographed on 9 May 1970, one week after receiving this honorary degree, Wilkinson stands beside newly appointed D Litt, artist and lecturer Lloyd Rees (right) having attended the ceremony to honour his friend and former colleague from the Faculty. Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives G3-224-1081.

Travelling and drawing: studentships, 1905-1909

The many prizes and studentships won by Leslie Wilkinson during his years at the Royal Academy gave him the chance to travel, firstly within England and later in Europe, studying landmark buildings and drawing them. At this he would prove particularly gifted.

In 1905, he toured though England drawing cathedrals, university colleges, villages and individual houses that caught his interest. The following year he travelled, bicycling, through Spain, France and Italy. Here the quality of the light, and the colours of both the natural and the built environment were a revelation to Wilkinson’s artistic sensibilities. The lessons he learnt as he experienced and appreciated the unfamiliar world around him, and experimented with reproducing what he saw in his drawing, would later inform the architecture he produced in Australia, where he recognised the similarity of landscape and conditions.

During his tours he took an holistic approach to his self-education, describing his strategy in every place as one of ‘taking a broad interest in the allied Arts, examining the world famous collections and studying modern problems in town and country.’ [43] Wilkinson was already aware that architecture cannot be separated from what surrounds it or what it serves.

Leslie Wilkinson would advocate throughout his life for the opportunity for architects, and students of architecture, to travel and view the work of others in its local context.

Our students must travel. And we must aid those who would not otherwise be able to do so by means of travelling studentships or bursaries, awarded in competition.

Travel, a valuable means of education in most subjects, is obviously of supreme value to the student of architecture.

"University of Sydney, School of Architecture, Inaugural address, 4 September 1919/ Professor Leslie Wilkinson in Architecture : an Australasian review of architecture and the allied arts and sciences Vol 6 No 320 September 1919 p. 69.

For Wilkinson, success begat success, and as he returned from his studentships with more examples of his skilled draughtsmanship, these in turn would win accolades. The RIBA medal he won for measured drawings in 1908 recognised his rendering of the Gran Guardia Vechia, Verona, undertaken during his studentship tour of Italy in 1906. Apart from the excellence of execution, that work had the distinction of being the first known measured drawing made of the building since its completion. [44]

Wilkinson made full use of the opportunities granted to him, and would be amply rewarded by his own talents and labours.

“ The complete collection of English and European drawings from the period 1900 to 1908, of surprising quantity and quality, later formed a valuable reference which Wilkinson would draw on for the rest of his life

Wilkinson, David "Early days" in Leslie Wilkinson: a practical idealist p. 16

Skilled as he was, Leslie Wilkinson had firm views on the place of draughtsmanship in the broader scheme of architecture, a former student at Sydney recalling:

“ he deplored the false value given to draughtsmanship for its own sake. ‘An Architect’s work is to produce buildings, not drawings,’ he would say as he presided over the ‘ruination’ of some unhappy student’s finished rendering in order that the design might be improved.

J L Stephen Mansfield in Architecture : an Australasian review of architecture and the allied arts and sciences Vol. 36 No. 4 1 Oct 1948 p. 37

Conversely, a great compliment for a student’s drawing was, ‘that will build well.’ [45]

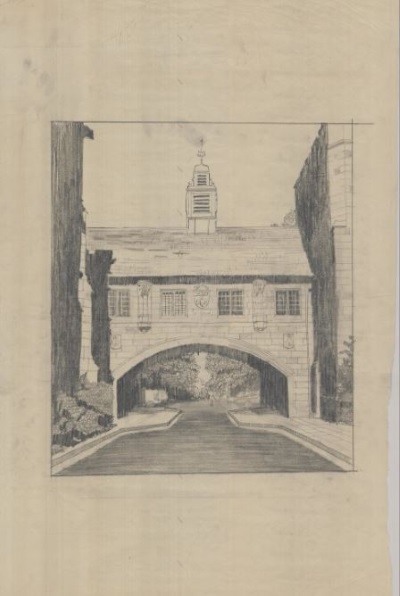

Despite his own views, Leslie Wilkinson would be admired throughout his career for this auxiliary skill, so it is fitting that his last appearance in public would be at the opening of an exhibition of his drawings, in a setting that summed up much of his life’s work. The exhibition had been curated by the university archivist, and was displayed in the University’s War Memorial Gallery of Fine Arts, housed in rooms within an archway over Science Road –a space that he had shared in creating.

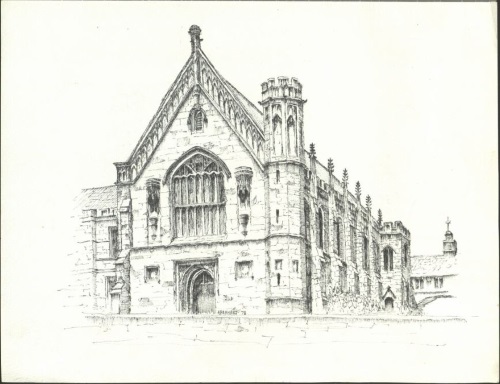

The launch itself was held in Edmund Blacket’s Great Hall, of which Wilkinson had said in his inaugural address to the University in September 1919, ‘Who, for instance, seated in this Great Hall, will deny that a building can communicate emotions? This Hall thus possesses one of the greatest attributes of Architecture.’ [46]

Fifty-four years later, on 17 October 1973, a month shy of his ninety-first birthday, Wilkinson is remembered to have stood firmly and without assistance as he gave what would be his final address - ‘a good short speech of thanks to those who had been responsible.’ [47]

Drawing of the Great Hall, including a partial glimpse of the arch over Science Road which houses the War Memorial Gallery

Creator unknown. Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF REF-00047790

Early career as a practitioner and the move to academia

Having stayed the course of his three years articled to James G S Gibson, Wilkinson’s career as a practitioner began in 1903 in the same office. The firm regularly dealt with public and municipal buildings – libraries, galleries, museums, town halls – as well as commercial work, such as banks and office blocks. Typically, the public work was won in open competitions, and Wilkinson retained a lifelong interest in these exercises – imperfect as he thought the process as a means to its intended result. Over the next five years, as he completed his Royal Academy studies and took time for studentships, the work with James Gibson provided important experience for Wilkinson in overseeing individual projects and the broader administration of an architecture firm.

Impressed by Wilkinson’s abilities, and generous as an employer, in October 1908 Gibson encouraged him to apply for a position at the School of Architecture, University College, London as assistant to Professor Frederic Moore Simpson.[48] Presenting for interview in a top hat and tailcoat – a tactic he would also employ when applying to the University of Sydney a decade later – Wilkinson was the successful candidate.

The employer who farewelled him in 1908 would demonstrate nine years later that his confidence in his former pupil remained undimmed. James Gibson, writing in 1917 in support of Wilkinson’s application to the University of Sydney, declared that Wilkinson ‘would vitalise the study of Architecture and impress Students with the fact that it is a living Art’. [49]

Wilkinson’s new superior, Professor Frederic Moore Simpson, had come to the University of London from the School of Architecture at the University of Liverpool. The London School was the older of the two, established in 1841 under eminent architect Thomas Leverton Donaldson, co-founder of RIBA and a pioneer in architectural education. However, the Liverpool school was the first school of Architecture in the United Kingdom to be affiliated with a university, and the first to achieve degree programmes validated by RIBA. Between 1894 and 1904, Professor Simpson had been the first Roscoe Professor of Architecture at Liverpool, developing programs and educational strategies, just as Leslie Wilkinson would later do at Sydney. It is likely that Simpson’s experience presented Wilkinson with valuable opportunities to discuss key principles in this undertaking, storing away this knowledge for the future.

Beyond his teaching life, Simpson was a noted exponent of the Arts and Crafts movement, and was the editor of the multi-volumed History of Architectural Development , published in stages between 1905 and 1913, and still in development when Wilkinson arrived at University College. Simpson would incorporate Wilkinson’s drawings in the third volume, and indicated in his preface that his junior colleague had also redrawn some of Simpson’s own work for reproduction within the history.[50] This was a generous and no doubt sincere acknowledgment of Wilkinson’s drawing skills.

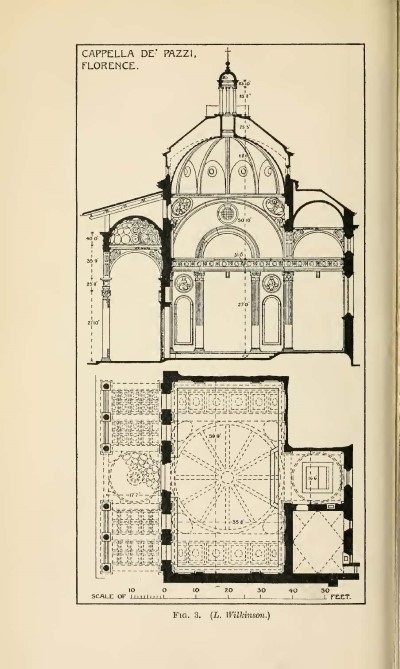

Leslie Wilkinson’s drawing of the Cappella de’ Pazzi, Florence as reproduced in Volume III of Frederick Moore Simpson’s History of the development of Architecture .

Leslie Wilkinson would spend ten years as Frederick Moore Simpson’s assistant, cementing his position rapidly with his appointment as Assistant Professor in 1910.[51] The teaching experience he would bring to Sydney was formed across this decade in his life. He gave lectures, both to students enrolled in the School of Architecture and to attendees of the University’s Evening School of Design. He supervised classes in drawing, and accompanied students on tours around England to sketch and study buildings.

With the outbreak of war and his enlistment, his energies were divided between duties at the School of Architecture and service in the University of London’s Officer Training Corps, both undergoing training and lecturing in Topography and Field Engineering at the training depot. His war service later developed into command of an infantry company of the Territorial Force, commissioned with the rank of Lieutenant.

Over these same years, Wilkinson took steps towards the establishment of his private practice, taking on a variety of projects, including a surgery and chapel at the Wellcome Institute in Millwall, and the gymnasium and science laboratory of a Grammar school, as well as various domestic architectural projects.[52] His mentor, Frederick Moore Simpson involved him closely in the design and delivery of a number of buildings for the university, including in 1911, a dedicated building for the School of Architecture – the first such purpose-built headquarters for an architectural school in Great Britain.[53] As with so much of his experience gained at the London University College, involvement in this exercise provided Leslie Wilkinson with skills and understanding he would later usefully summon at the University of Sydney, when he assumed the role of University Architect in 1919. While this would prove a less than happy experience for him, it produced many buildings on the Sydney campus that have stood the test of time.

The years following Wilkinson’s qualification as an architect provided a diversity of experience and opportunity, which he seized and exploited fully. He was aged thirty-five and ready for new challenges when the next opportunity presented itself.

An academic opening in the colonies

In December 1916, it was announced in the Sydney press that the government had endowed a Chair of Architecture at the University of Sydney, founded on the sum of £2,000 per year. The move was seen as long overdue by The Herald, which noted that there had been appeals for this provision since the early 1880s. There was further reference to Australia’s loss to Europe and America of gifted Sydney youth, forced abroad for the want of a local degree course in architecture.[54]

The reality in 1916 was perhaps less extreme than suggested by the Herald’s account. Just as England’s architects of this era still qualified through a variety of means outside a university - Wilkinson himself an example of this model – trainee architects in Sydney were not without educational options to supplement the office learning of their articles. A diploma in Architecture was one of a range of non-trade courses provided by the Sydney Technical College, [55] the designation ‘ASTC’ attached to many highly regarded Sydney architects of the time, some of whom Leslie Wilkinson would variously admire, befriend and work beside.[56]

Moreover, since 1884 the University itself had offered an annual series of lectures in architecture as part of the third year of a certificate course in engineering, which had been added to the Faculty of Science in 1882. The course of lectures was presented at night, and access was not restricted to students enrolled in the full course of university study, making it an attractive supplement to the education of trainees under articles, and students of the Sydney Technical College. From their inception, these lectures had been delivered by a succession of prominent architects engaged by the University – Cyril Blacket, John Sulman and John F ‘Jack’ Hennessy. From 1896, through the apportionment of a major gift to the University from Peter Nicol Russell, [57] an endowed lectureship in Architecture was funded through the Department of Engineering, providing certainty for this program.[58]

Nevertheless, the Heraldwas correct in noting that the campaign for a Chair had been long, and beset with frustrations and obstacles beyond the control of the key players. A century later it would be remarked that, “It is no exaggeration to describe the early history of architectural education at the University of Sydney as a history of initiatives thwarted by circumstances.” [59]

By 1916, the local profession saw much at stake in lifting the education of architects into the realm of the university. The issue of educational status was seen as critical to a simultaneous push to introduce a local system of registration for practitioners, regulating the use of the professional title ‘Architect’ to those appropriately credentialled.[60]

If press coverage is an accurate reflection of public sentiment, it would seem that Sydney people had no small interest in the endowment of the Chair of Architecture. The daily newspapers gave regular updates on the progress made by the University Senate towards filling the vacancy, and attached broad hopes to the outcome. The Heraldpronounced the development as a first for the British Empire, and the means of making Sydney ‘the architectural centre of Australasia’.[61] Ada Holman, journalist, feminist and the wife of the New South Wales Premier, publicly mused upon what implications the new course might have for women who were interested in a career in architecture. [62] The Premier himself claimed the appointment would ‘educate the people of Australia to appreciate the architectural differences between a galvanised iron stable and the Cathedral of Notre Dame.’ [63]

This was the historical background against which the new professor at Sydney would take up the Chair. It was by no means a blank slate, and complicated by more immediate factors besides. With the first students in the new course scheduled to begin studies prior to the appearance of the new Chair, an initial curriculum was prepared of necessity by the then serving P N Russell lecturer in Architecture, Jack Hennessy - creating a first challenge to be dealt with on arrival by the permanent appointee. As a leading figure in the NSW Institute of Architects, Hennessy had also been instrumental in the drive for the establishment of the Sydney Chair, therefore had a keen interest in its sequel, and furthermore had been considered a home-grown alternative for the position.[64] In this last, Hennessy was supported by some members of both staff and Senate of the University, in a reaction since described as ‘a brief burst of that parochialism which emerges from time to time at Sydney University.’ [65]

Tact, competence and unassailable authority would be required of the successful applicant for Sydney’s Chair of Architecture, whose task it was to draw together these disparate historical threads into a workable whole.

“Professor Leslie Wilkinson, A.R.I.B.A.

Chair of Architecture, Sydney University”

This portrait of Leslie Wilkinson in his British service uniform was published as the frontispiece to the March 1918 issue of the Institute’s journal Architecture.

Reproduced from Architecture: an Australasian review of Architecture and the allied arts and sciences being the official journal of the Institute of architects of New South Wales, Queensland , South Australia, West Australia and Tasmania.

Earning a colonial appointment, 1918

In seeking to fill the new Chair of Architecture from abroad, the University of Sydney was following established practice. The Senate appointed three professors in February 1918, only one of which had not involved recruitment in London – although the Chair of Architecture was ultimately the only one filled by those means. [66] Early in 1918, the University Senate assembled a selection committee in London to review applications for the position, working through the Agent General of New South Wales, which also had representation on the panel.

For his part, Leslie Wilkinson would later wonder if he might never have been aware of the vacancy at Sydney had it not been for his wartime service with the University of London’s Regiment. The advertisement appeared in a scientific publication from the New South Wales Agent General’s Department, his attention drawn to it by his commanding officer. Wilkinson’s grandson David would write of his grandparent’s reaction to the opening in Sydney: ‘He and his wife decided, for a number of reasons including health, a sense of adventure and hopes for a great academic future, that he should try for the position in the colonies’.[67]

With the encouragement of Professor Simpson, and supported by ten other impressive referees, Leslie Wilkinson created an application that was outstanding not only in what he had to claim for his candidature, but in its visual presentation - ‘no ordinary handwritten letter, but an application designed with all the style and panache he was later to demonstrate in so many ways.’ [68] Pleasing in layout and lucid in expression, the document was also professionally typeset and printed, in a clear challenge to lesser standards.

Professor Simpson was himself on the London selection panel for the Sydney position, as were two other of Wilkinson’s referees. Given the relevance of Leslie Wilkinson’s experience to Sydney’s needs, and the standing of those members of the English profession who were willing to speak for him, it was unsurprising that he was the successful applicant.

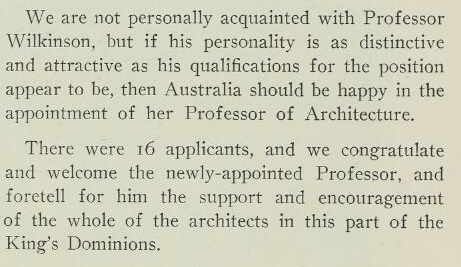

In Sydney, the appointment was roundly embraced.

Extract from Architecture: an Australasian review of architecture and the allied arts and sciences being the official journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, West Australia and Tasmania Vol 3 No 2 February 1918 p. 44.

Making his way via Canada and North America, Wilkinson travelled alone to Australia, his family to follow later. He visited the School of Architecture at Harvard, and studied the architecture of American practitioners who had piqued his professional interest, especially admiring the work of architect and landscape designer Charles A Platt. He arrived in Sydney on 19 August 1918 to a city that was eager to meet him.

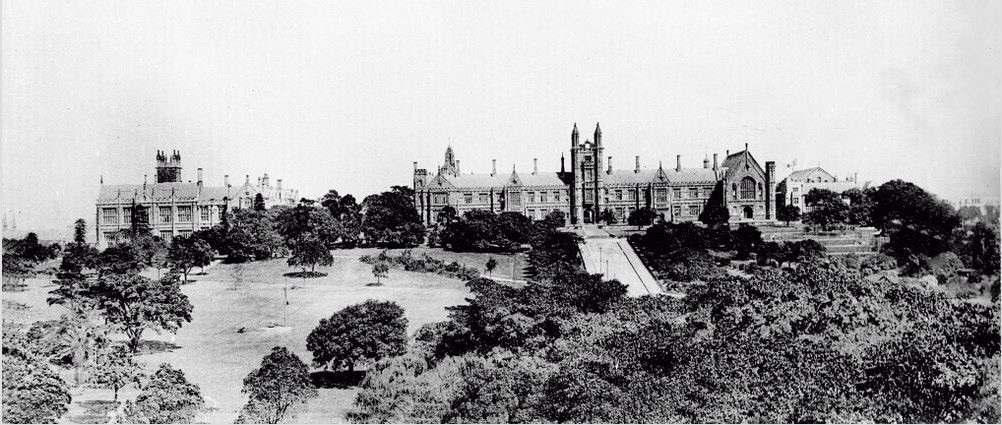

It was claimed – from far-flung Melbourne - that Leslie Wilkinson “was only an hour or two in the Harbour City, when he set forth to have a look at the buildings,” [69] a picture in keeping with Wilkinson’s always-lively interest in his surroundings of the moment. A more restrained account of his arrival reported a welcoming party of members of the University and the Institute of Architects, followed by a meeting with “Mr Barff and several of the Professors.”[70] It is likely that this meeting drew Wilkinson towards his first glimpse of the main ‘Blacket’ buildings of the University, said to have rendered him “amazed and elated,” pronouncing the Great Hall to be, “as good if not better than any Gothic Revival building in England.” [71]

Great Hall and main range, 1910s, courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00053603

Other aspects of the grounds, and the lesser buildings that abounded, appear to have left his aesthetic eye disappointed and immediately envisioning improvements. He later recalled

“Buildings were just dotted around and the grounds were in an extraordinary state – buildings fenced around with iron railings with horses grazing outside…like the morning after the fair, with a few little wooden huts scattered about.’

Leslie Wilkinson interviewed by John Thompson, ABC c1965, quoted in Johnson, Peter "Leslie Wilkinson at Sydney University” inLeslie Wilkinson: a practical idealistp. 60

The dichotomy typified what Wilkinson found in early twentieth-century Sydney - a natural environment which he considered to have extraordinary aesthetic appeal and potential, complemented in places by excellence in the man-made contribution, but overlaid too generally with mediocrity, amounting to a squandering of opportunity. “Sydney has one of the most magnificent sites in the world, but it is not the most beautiful city in the world,” he would say.[72] Where he met excellence he was generous in its praise, prepared to fight to protect it,[73] and if commissioned to work with it, vigilant in respecting the original intent and design of its creator.

The new Professor’s reception in Sydney gives an insight into the status accorded senior academics of the University, and the institution itself, by the government and other sectors of the City. This in turn gives insight into the broad expectations vested in Wilkinson and his role, and into his personal understanding of his mission, which was by no means restricted to the education of the students enrolled in his courses.

Wilkinson at the outset expressed great encouragement in what he interpreted as the “striking unanimity”[74] demonstrated between Government, University and the architectural profession in the establishment of a Chair of Architecture. He saw it as his responsibility to build on this cohesion. He had been appointed as a Fellow of RIBA in 1918, and less than a year after his arrival in Australia, in April 1919, Leslie Wilkinson was elected to the Council of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales.[75] He served as its President in 1933, and with the foundation of the NSW Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of architects in 1933, became its first president.[76]

Wilkinson was formally welcomed to Australia at vice-regal level over tea at Admiralty House on 29 th August 1918.[77] On 5 September 1918, members of the Town Planning Society hosted Wilkinson at a luncheon for its members and guests at Farmers,[78] a smart city department store of the day, complete with a restaurant and roof garden.

On the same day, Wilkinson was the Guest of Honour at an ‘at home’ held by The Institute of Architects, where guests included the Premier of NSW, William Holman, and a number of Ministers of the NSW government.[79] The function was held in the rooms of the Royal Society of New South Wales, a long-established organisation for Sydney’s scientific elite, of which numerous of Wilkinson’s new colleagues were members. William Sutherland Dun, the Royal Society’s serving President in 1918, and a lecturer in Palaeontology at Sydney, was one of those present to greet him. The Society’s rooms in Elizabeth Street were housed in the same building as the Institute of Architects’ office, so convenience probably dictated the choice of venue. But it was a reminder that the Chair of Architecture fell under the Faculty of Science.

Throughout this introductory period, the mainstream press was eager to glean and relay Wilkinson’s views on matters of interest to their readers. The receptions held by the professional bodies were noted in the pages of the dailies, and were also given detailed coverage in official industry journals.[80]

Wilkinson no doubt allowed a certain cautious reserve to limit his responses, and appears to have said considerably less than most of the other speakers on these occasions. Nevertheless within what has been recorded of his early pronouncements lay indications of what he stood for, and pointers to what lay ahead. He appears to have spoken most expansively with the Herald, resulting in a report published just three days after his arrival that summarised those of his beliefs, plans and hopes that he was prepared to share:

On the responsibility of the university’s teaching to the community :

“The aim of the new school would be to give students a sound qualification for practice, and to create an interest in architecture and town-planning for the benefit of the community in general.

On the significance of architecture to sound town planning :

“The architectural aspect, which was one of the most vital aspects of town-planning, would receive full attention at the new school, and this should widen the scope and interest both of the regular student and of the body of citizens.

On the importance of good design:

“The scheme of training would be to give the student a sound and comprehensive grounding in the principles of design, which skilfully applied, should result in the production of good buildings, ranging from the simplest domestic work to the most imposing of civic monuments.

On the desirability of a university education for architects:

“Architecture, touching as it did the lives of us all at every point, and requiring in its practitioners a breadth of outlook, sympathy, and feeling, combined with a working knowledge of many of the sciences, was obviously a subject which could only be thoroughly dealt with in a university where the best services of experts in the many and diverse subjects would be available to the student.

On the natural and built environment of Sydney:

" Although I have scarcely had time yet to see Sydney, I have already been greatly struck by its fascinating topography and the amount of good architectural work with which it is embellished.

On whether Australia might develop a style of architecture of its own:

“All sound schemes of education must be based on the work of the past. But such traditional work must be used as a willing servant, and not be allowed to blind us to the modern problem under Australian conditions."

"Architecture." The Sydney Morning Herald22 August 1918 p. 8.

University of Sydney, 1918 – 1947

Leslie Wilkinson began his educational leadership at Sydney in mid-September 1918 at the start of the Michaelmas term, and he would retire at the close of the Michaelmas term in December 1947. The intervening twenty-nine years were marked by sound progress and many notable achievements, both for university and professor, and Wilkinson would remain a respected figure at their close.

However, his was by no means a trouble-free tenure, and certain of the challenges he faced were, at least in part, of his own making. Before he had been in the role for ten years, criticism would force the modification of the course he had designed with such assuredness in 1918, when he had lost no time in overhauling the temporary curriculum devised by his predecessor, Jack Hennessy.[81] In parallel with these disappointments, his grand vision for the University site, and his involvement in its delivery, devolved into a sad episode of disagreement and recrimination, with only part of what he had hoped to achieve ever realised.

Wilkinson's early years at the University were promising. His arrival coincided with post-war growth in demand for university-level education across a widening range of knowledge areas. This led to the subdivision of the four existing faculties at Sydney – Arts, Science, Medicine and Law – into ten new faculties. At the time of this development, the enrolment in Architecture was one of the smallest in the university, and the four-year course so recently introduced that the degree established as the Bachelor of Science (Architecture) had yet to be awarded to its first enrolees.[82] Despite this, the Faculty of Architecture was one of the ten created.[83] This must have been in no small measure due to the persuasive arguments of Professor Wilkinson, and the University’s confidence in his abilities. It would have been a considerable endorsement when Wilkinson was announced as the Dean of the new Faculty of Architecture in July 1920, [84] less than two years after taking up his appointment as the Chair.

Likewise, five years after Wilkinson’s initial appointment to the Chair, the local professional body expressed an unshaken belief in the education that the University had made available to students of Architecture. In his Presidential address to the Institute of Architects (NSW) in 1923, Sir Charles Rosenthal remarked:

“It must also be very gratifying to the members of our Institute to see so many students taking up the architectural course at the University. Those of us who served our articles many long years ago under very different conditions, appreciate more than the students of today do, the wonderful opportunities now given them. In the years to come, those who were trained at our University will be a very definite source of strength to this Institute.

("The Architects" Construction and Local Government Journal21 March 1923 p.12.)

However, within only a few years, complaints that had their genesis in course content and direction had arisen regarding the quality of graduates from the new Faculty. In late 1922, the long-awaited system of registration for architects had been introduced following the passage of the Architects Act, No. 8, 1921,[85] and a Board of Architects established. Wilkinson was among the appointees to the Board, ex officio.[86] But the process and the new body would expose problems in the course of study offered under Sydney’s first Dean of Architecture. The nature of these problems is laid bare in a centenary history of the School of Architecture:

“Early graduates of the Faculty of Architecture were not, upon graduation, considered technically competent, which created trouble with their registration. Architects who graduated from the faculty were entitled to be registered, but the NSW Board of Architects, as the statutory registration body, was unhappy with the class of graduates being admitted to their ranks”

Ryan, Daniel J “Architects in white coats” inSydney School p. 76

It was presumably an astonishing revelation, at least outside the Faculty and Board , and a state of affairs at odds with what Wilkinson had promised in his inaugural address, when he had spoken to the ideal of well-rounded and fully equipped graduates, ready for practice.[87] Moreover, since the introduction of a university course in Architecture had been seen as a necessary precursor to registration, as well as a foundation for the bedding down of professional status, the irony of the situation would have been inescapable, making matters all the more awkward for the University.

While blame may be assigned to Wilkinson as the head of the Faculty, dereliction should not be assumed to be the cause. Wilkinson was energetic, efficient and passionate in his role. He was undoubtedly ambitious for both his discipline and his students. He wanted his students to be leaders, not just within the profession, but leaders of the profession. This was to be achieved by virtue of the high standard of their education, and of more elusive attributes which he saw it as his responsibility to foster. His goal was to create, “A body of true students of architecture with a great love for their art, with skills, enthusiasm and ideals.” [88]

He likewise held firm views on the primacy of Architecture among the Arts, defining it as “the mistress art,” [89] which led all others. This conviction informed his personal teaching, shaped the curriculum he built, influenced the selection of staff he employed and determined the hours of the Faculty’s teaching time allocated to various subjects and pursuits within the course. The emphasis was heavily weighted towards design, aesthetics, and the cultivation of “taste” – a quality to which Wilkinson frequently alluded, claiming that without it “the highest technical ability will be of no avail in producing successful architecture.” [90]

If Wilkinson is to be criticised, it is perhaps for an overly zealous application of his personal philosophy. Within that educational environment, a deficit developed in attention to the technical, legal and practical aspects of an architect’s career.

Professor Wilkinson was away on a first sabbatical from his Sydney position when matters reached a head. In his absence, funds were hurriedly found to create a new Associate Chair of Architectural Building Construction. Alfred Hook, a part-time lecturer in Construction since 1922, was appointed.[91]

An immediate remedy had been applied, but not without damage. It was a humiliation for Wilkinson personally, and for the University, driven to take direction from external forces on matters wholly under its remit. The solution also fractured the Faculty, with attendant professional rivalries and tensions unleashed. The situation would never be fully reconciled during the working lives of Alfred Hook and Leslie Wilkinson.[92]

The story of Wilkinson’s period as University Architect, from 1919 to 1928, presents similar contradictions. On the one hand are the extraordinary architectural achievements that live on in the University’s built environment, and on the other, the regrettable termination of an appointment for which Wilkinson would have seemed eminently qualified and suited. While budgetary mismanagement lay at the heart of the problem, Wilkinson’s handling of the situation on a personal basis lacked the finesse that might have spared him the harsher judgement he ultimately received.

“No doubt his strong personal convictions and autocratic attitudes contributed to the breakdown. No doubt the precedence he gave to visual architectural aims, especially those involving external appearance over more mundane questions, also contributed.

Johnson, Peter “Leslie Wilkinson at Sydney University” in Leslie Wilkinson: a practical idealist p. 68

Wilkinson had arrived at Sydney with the expectation that as Professor of Architecture he would also assume the role of University Architect, the model he had observed at University College, London. Upon discovering that in New South Wales, the Government Architect performed this function, and impatient to instigate and control improvements where he could see so much was needed, Wilkinson used an appointment to the University’s Buildings and Grounds committee to great effect.

In his capacity as a committee member, Wilkinson discovered a group of ready allies among colleagues of his own faculty (still at that time the Faculty of Science) who were pressing the urgent need for expanded and improved teaching accommodation. When a plan sought from the Government Architect’s office for additions to the Organic Chemistry Department was not forthcoming to deadline, Wilkinson produced a set of his own drawings at the committee table. These were approved by the meeting, and ultimately the Government Architect’s office was instructed to act upon them.

University petitioning had at this time borne fruit in the quest for government assistance to cope with the post-war growth in enrolment. A grant of £300,000 had been awarded specifically for expenditure on buildings, to be issued in instalments of £50,000 over a six-year period. Thus the means were suddenly available, and Wilkinson was well on the way to having the authority to implement his creative vision.

By the end of 1919, under a resolution of the University Senate, Wilkinson was ‘firmly in position’ as University Architect. Furthermore, the Minister for Education had explicitly referenced his supervisory role in a memorandum with regard to the approved expenditure for the University. By August 1920, Wilkinson’s first buildings for the campus - the Organic Chemistry Building and the Physics Building – had received formal assent to proceed. In the words of a later Dean of Architecture, “The Government Architect’s response is not recorded – but a long, slow fuse had been lit.” [93]

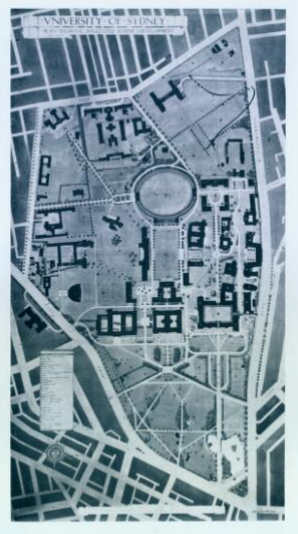

His involvement in the Buildings and Grounds committee also played into Wilkinson’s hands in coinciding with a Senate request for a plan for the layout of the University grounds. Just as he viewed Town Planning and Architecture as intrinsically integrated disciplines, Wilkinson saw the need to establish an overall scheme for the University lands to create an appropriate setting for well-designed buildings – both those already in place and those that would follow. On the committee’s recommendation, the work of creating the plan was delegated to Assistant Professor Madsen of the School of Engineering, Alexander Donald Craig, Lecturer in Surveying and Professor Leslie Wilkinson.

In examining previous surveys, Wilkinson discovered that in 1915, American architect, landscape specialist and planner Walter Burley Griffin had been commissioned by the University to provide a plan for its property. The work had been completed and submitted, but never adopted, and had then been superseded by a similar exercise by the Government Architect’s office in 1917, likewise buried. Disregarding the later work, Wilkinson focused on Griffin’s, of which he would say:

“The plan, unfortunately, seems to have been ignored; it is drastic, like most good remedies but shows a fine grasp of a big problem, and it seems a pity that it was not to some extent at least acted upon.

Wilkinson, Leslie “The Architectural development of the Sydney University...” Building: the magazine for the architect, builder, property owner and merchant , Vol. 28 No. 164, (12 April, 1921) p. 56.

Under Wilkinson’s steering hand, Griffin’s scheme was developed and refined into the masterplan submitted to the University Senate in January 1920, and adopted two months later. The plan addressed both major themes and smaller, practical concerns. It’s scope ranged from the creation of ‘centres of interest’( ie the grouping of buildings into precincts dedicated to interrelated areas of study) to the burying of unsightly electrical wires and the need for perimeter fencing of the entire site to allow for the dismantling of unattractive internal fencing.[94] But its primary concern was to capitalise on the best of the site’s natural features and to impose unity and order throughout.

The visual experience of the site was naturally an overriding consideration, some of Wilkinson’s most effective results achieved by either preserving or opening up vistas to heighten the viewer’s awareness and appreciation of the existing landscape and landmarks. Wilkinson’s vision was partially realised through ‘carefully placed axes with intriguing sequences of open and closed courts.’ [95]

His goal was to exploit the 'attractive topography' of the land and to accentuate the ‘skilful placement’ of the Blacket buildings (the Great Hall, ‘main or Eastern range’ and St Paul’s College). [96] Blacket had set these key buildings on the commanding Petersham ridge overlooking Victoria Park, presenting a powerful visual statement on approach from the City – the positioning of the building acknowledged as ‘a conscious statement of the importance of the University.’ [97] Wilkinson worked to preserve the effect that had so impressed him on his first view of this scene, in August 1918.

Looking towards the university across Victoria Park. Blacket’s ‘main’ Buildings (at right) and Anderson Stuart Building (at left) 1928.

Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00009777

In this, the 1920 Masterplan plan reflected Wilkinson’s customary respect for what had come before him. His approach to preserve and enhance worthwhile existing features set a principle that has prevailed on the University site, as the for the State Heritage listing of the University testifies:

“Overall, many features of the University of Sydney and University Colleges retain their integrity from the date of their establishment. Such features include the alignment of the site, boundaries and their treatments, the internal layout of many of the roads, the configuration of buildings and gardens and the uses of a number of the buildings and precincts.

Statement of Significance (Integrity/Intactness), State Heritage Listing, The University of Sydney, University Colleges and Victoria Park, State Heritage Inventory, Heritage Office of NSW.

Wilkinson’s masterplan would never be delivered in its entirety, overwhelmed by many factors in the history of the University – in particular, the post-World War II urgency to accommodate another sudden and extreme influx of new students. Enough of his work has survived, however, to inform and enrich key areas of the present-day Camperdown campus, delivering Wilkinson’s goal to create “a sense of unity, order, convenience and it may be, eventually, beauty, into the University quarters, treated as a whole.” [98] This was not only an aesthetic objective, but an aim to create the environment which Wilkinson felt best supported and enriched student life.

“pleasant places to stroll and dream dreams – dreams which will bear fruit in the work of lives, the life work of the men and women with whom rests the destiny of the ‘Great University’ – the Commonwealth.”

Wilkinson, Leslie “Collegiate architecture” in Architecture : an Australasian review of architecture and the allied arts and sciences Vol 20 No 9 1 September 1931.p. 202

What survives on the Sydney campus – and much does – is an exemplar of his philosophy.

The University of Sydney – Wilkinson’s 1919 plan

reproduced from Art in Australia

Series 3, No 31 1 March 1930

“Strongly associated with Professor Leslie Wilkinson and the implementation of his 1920 master plan, the University grounds, more than any other site, reflects Wilkinson’s work in beautifying and unifying buildings and their settings.

The University of Sydney Grounds Conservation Management Plan p. 97

With a Masterplan adopted, Wilkinson’s attention turned to the structures that would occupy it. These would be his first buildings in Australia, and the distinctive themes and devices seen in his later private commissions were already discernible in the transformation he set in motion at Camperdown. From the formative attention paid to the site, the preference for clean, neo-Georgian lines, the recognition that Mediterranean rather than British-inspired design best suited Australian conditions, to the subtle and restrained use of decorative detail to lift the finish above the ordinary – all the Wilkinson characteristics are evident.

Eight projects were agreed upon for Wilkinson to deliver with the government grant moneys:

1. Lecture room for applied chemistry

2. New building for Department of Physics

3. Additional building for Mechanical Engineering

4. Completion of Quadrangle for administration and Arts

5. New building for the Department of Chemistry

6. Completion of gap in north end of Medical School for pharmacology

7. Department of Anatomy: Dissecting room and examination hall (for whole University)

8. Cloisters in Quadrangle [99]

Wilkinson would draw on some of the most talented architects and prominent firms in Sydney to assist him in these works : Hardy Wilson (Wilson Neave and Barry), B J Waterhouse (Waterhouse & Lake), R Keith Harris, Joseph Fowell, John D Moore and R Richardson.[100]

As with his approach to the plan of the University grounds, Wilkinson looked first to the past, as an aesthetic anchor for his own building program.

“… we must be struck by the good fortune of the Senate in finding ready to serve them, Edmund Blacket. The work on the main range and Great Hall was begun in 1854 and finished in 1860 and, as you know, gave Sydney in the Hall at any rate an architectural masterpiece of the first rank; in fact, the finest of its type in Australia and one which can hold its own with many in the old country”

Wilkinson, Leslie “The Architectural development of the Sydney University...” Building : the magazine for the architect, builder, property owner and merchant , Vol. 28 No. 164, (12 April, 1921) p. 56.

Gifted this starting point, Wilkinson took care to complement rather than overpower the existing structures, considering not only the Blacket work, but other major buildings which contributed to the main quadrangle precinct. These neighbours included James Barnet’s 1890 Medical School (also known as the ‘Anderson Stuart building’) and the original Fisher Library (now MacLaurin Hall) built between 1903 and 1909 under Government Architect Walter Liberty Vernon.

The western and southern facades of the newly built Fisher Library (now MacLaurin Hall) c1910. Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00021952

Wilkinson employed subtle devices to unify the existing work of his predecessors, and to ensure his own additions blended with the whole. He took an approach that has been described as ‘deliberately discontinuous,’[101] using stylistic variation across sections he built that linked or bordered existing buildings. This acknowledged the organic growth of the complex, while achieving compatibility. The strategy avoided jarring transitions and preserved the integrity of the original. By the late 1920s, his infill buildings on the ‘main’ section of the campus had formed the basis of the quadrangle, awaiting further stages in his overall plan to be taken up when funds allowed – most notably, an extension continuation of the cloisters, which was carried out in the 1960s, but with considerable modification to his design.[102]

“Completion of the quadrangle”, 1927 - drawing by Leslie Wilkinson.

Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00049353

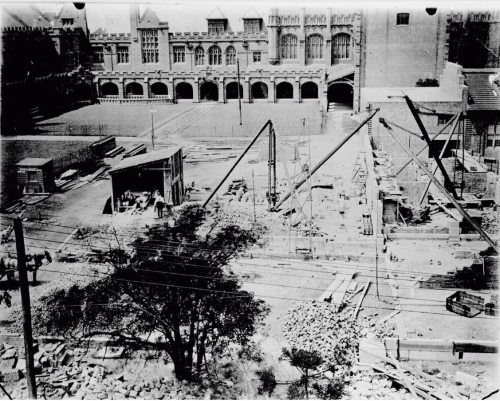

The Administration Building under construction in the 1920s. In the foreground can be seen the overhead electrical wiring to which Wilkinson so strongly objected – ‘crude posts with their webs of wire which even invade the main quadrangle!’ (Inaugural address in Architecture Vol 6 No 3 20 September 1919 p. 76.) Image courtesy of the University of Sydney REF-00054972.

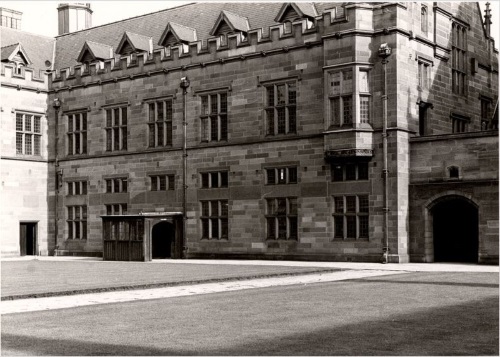

The administration building photographed in the 1960s. The porch at ground level was a contentious addition made when Wilkinson was on sabbatical, and finally removed in the 1970s. (Johnson in Practical idealistp. 75.) Image courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00046357.

Beyond additions, remodelling and infill structures, Wilkinson also delivered complete facilities. The most striking of these was the Physics Building – prominent in scale and siting as well as its arresting neo-classical form. Wilkinson chose to move this department away from its former home in Science Road, to a position separated from the already developed campus by a square of dedicated open space. A land exchange with St Paul’s college was organised in order to achieve this – the second of such arrangements made in the mid-1920s when the University also exchanged land on its eastern boundary with the Council of the City of Sydney, to allow for future building activity along Eastern Avenue.[103]

The physics building is shown in the middle ground of this oblique view of the University site in the 1930s Courtesy of the University of Sydney REF-00049582

The design of the new Physics building is said to have been inspired by Rome’s Villa Medici,[104] and an apparent homage to the 16th-century Lippi original can be seen in the form taken by Wilkinson’s paired towers, and their setting within the roofline. The long, low central section between the towers not only created a visually interesting height variation, but met the terms of a covenant attached to the land exchange with St Paul’s, safeguarding the northerly outlook enjoyed from the college. Wilkinson would have appreciated the college’s condition; opening up or preserving attractive vistas was part of his art, and the corollary was that the view to the Blacket buildings of St Paul’s from the northern side of the University grounds was also maintained.

The Physics Building photographed by Harold Cazneaux in 1927. Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00011866

The finish of the Physics Building is stylistically Mediterranean, with a whitewashed textured render overlaying the brick walls. Sandstone trim highlights the key features, most notably the imposing central entry, and creates a visual link with the stone of the main buildings. The building was completed in the mid-1920s, and the former Physics Building in Science Road (eventually re-named ‘Badham’) was made available to the Department of Electrical Engineering.

In contrast to the grandeur of the Physics Building, several of Wilkinson’s small scale contributions to the Sydney campus have been treasured by generations of academics and students. In the Vice Chancellor’s garden, completed in the late 1920s, he provided a peaceful refuge in the midst of one of the busiest parts of the campus, with part of the experience being the surprise of its contrast with the purposeful activity of the main quadrangle just beyond. Enclosed spaces would be a hallmark of Wilkinson’s architectural schemes, and whereas the main quadrangle exemplifies the form in the grand manner, the rendered walls and mullioned windows of the Vice-Chancellor’s garden offers a version on an intimate and human scale, with the building details homely.

A corner of the Vice Chancellor’s courtyard, 1930s. Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00050670

Integral to the success of this little quadrangle are the plantings of Wilkinson’s fellow Sydney academic Professor Ebon Gowrie Waterhouse, who was the McCaughey Professor of German and Comparative Literature at Sydney, but also a horticultural expert with a particular knowledge of camellias. The involvement of Waterhouse, in this case, came specifically at the request of the Chancellor, Professor Mungo MacCallum,[105] but Wilkinson and Waterhouse collaborated on a number of projects that enhanced the University landscape. It has been commented of their joint work that, “The pursuit of beauty, a guiding Interwar philosophy, informed their selection and placement of courtyard planting schemes, street tree avenue planting and character trees.[106]

A bronze statue was added to the courtyard inn 1953

Courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives REF-00076844

Another of Wilkinson’s works that proves the potential appeal of the small, rustic structure, when treated imaginatively, is his ‘roundhouse,’ or ‘Observation box’ for the Veterinary Faculty. This octangular timber structure usefully served for many years the practical purpose for which it was built: allowing students to witness veterinary procedures on large animals. The building was designed so that the demonstrator carried out this work in a central pit, while students occupied elevated seating, complete with built-in writing slopes, arranged around the edges of the building.

This was one of Wilkinson’s earliest works at the University, completed during 1921, and is the only one to have a superstructure built fully in timber, with weatherboard walls and a roof of wooden shingles. It is a departure from Wilkinson’s preferred Mediterranean style, belonging instead to the English vernacular.[107]

The 'Round House' - Veterinary Observation box, photographed in 1927 by Harold Cazneaux - Courtesy of the University of Sydney REF-00011880

Wilkinson frequently added roof decorations to his buildings, their style varying in keeping with the nature of each structure. The ‘round house’ sports a wooden ventilating lantern, topped with a weathervane featuring a dog, as opposed to the traditional cockerel. In this whimsical detail, Wilkinson was honouring the sphere of knowledge of the newly created Faculty of Veterinary Science. In the early 1980s, the need for extensive repairs to the weathervane’s mechanism posed a challenge ingeniously met by the University’s workshop, where the effort was a testament to the significance of this item, supporting the claim that the roundhouse is an icon of its precinct.[108]

As University Architect, Leslie Wilkinson exercised economies wherever he felt this would not jeopardise the quality of the result. The use of brick rather than stone for the majority of the Physics building, for example, was a stylistic choice that had its origin in a saving. Another saving was achieved when he twice sourced significant gifts of building materials, benefitting from demolitions elsewhere in the city. In 1922 he received 20,000 tons of stone through the Director of Technical Education, when work was carried at the former Darlinghurst Gaol. The following year he profited from the wholesale demolition of a large branch of the Commercial Bank in George Street, the University being given the stone salvaged from the ground floor and street-level facade.[109] Wilkinson would show the same resourcefulness when building his own house Greenway, recycling sash windows, cedar joinery and other timber detailing from a demolition site in Macquarie Street,[110] displaying a deft handling of the thrift inculcated by his childhood.

Clever and innovative as he was, it would be insufficient to rein in budget and stave off problems for Wilkinson. In 1922, several years into his time in the role of University Architect, it was discovered that votes for certain individual buildings had been overdrawn. The situation arose from a failure to include within the initial estimates the fees due to architects employed on projects, and the salary payable to the clerk of works. In this context, the Auditor-General began querying the management of such payments, and the wisdom and propriety of the University in employing its Dean of Architecture as University Architect.[111]

Taken to Cabinet and flushed into the public domain, this situation reached the Sydney press,[112] where it was presented in an unfortunately unflattering light, undoubtedly to Wilkinson’s personal distress, but also unsettling for all involved in the arrangements. In the end, structural changes were made to the management of these payments, which had the effect of unfairly reducing Wilkinson’s fees from the percentage basis originally agreed.[113]

Nevertheless, Wilkinson continued to work his way through his building scheme through the mid-1920s. As the limited government grant moneys continued to dwindle, Wilkinson began reassigning priorities extemporaneously, and openly prioritising the aesthetic over the necessary. This would cause strained relations with colleagues, who feared being denied much-needed new accommodation due to budget overruns and fund re-allocations. Two such competing priorities, and the consequences of decisions made around them, would finally see the removal of Wilkinson as University Architect.

One of the agreed eight projects identified for grant expenditure was a new building for the Department of Chemistry. In 1923, Wilkinson put forward an alternative, as a cost-cutting measure – to enlarge the current building with the addition of a second storey at its front, and to create further accommodation by constructing a ‘link’ building between the existing Chemistry building and the Badham Building - in 1923, still in use for Physics. Wilkinson’s proposal was to use the gift of stone from the Commercial Bank for this extension between the two existing buildings.

Professor Fawsitt, Head of Chemistry, who had been one of the first to welcome and provide hospitality to Wilkinson on his arrival five years earlier, was both unconvinced and openly disappointed by this new proposal. However, after much discussion, it was agreed that this variation in works should proceed. The pressure on Wilkinson to deliver a useful outcome through this compromise can be assumed to have been immense.

The second fateful issue emerged soon after. Professor Lawson of the Botany Department, in a letter to the Chancellor dated 28 September 1923, had aired a number of grievances. Alone of the Science departments, Botany – which had been moved some years before into part of the G A Mansfield-designed, 1887 Macleay Museum – had been allocated no improvements from the Government’s buildings grant. Moreover, the completion of the new Administrations Building (part of the main quadrangle) had seriously reduced the necessary natural light levels for effective teaching and microscope work in the Department’s main laboratory. An urgent appeal for new laboratory and other accommodation for the Department of Botany was put before the Chancellor, and referred to the Building and Grounds Committee.

On 15 October 1923, the Building and Grounds Committee met with Professor Lawson, with Wilkinson in attendance, and inspected the situation in the Botany laboratory.[114] The Committee then passed the following resolution:

"...to respond to the Senate that suitable laboratory accommodation be provided...for the Botany Department, if money could be found for the purpose, and that, if possible, the accommodation be provided in a building to be erected in front of the present Macleay Museum"

Minutes of the University of Sydney Building and Grounds Committee 15 October 1922 p. 72 University of Sydney Archives [REF-00003142]

Providing new accommodation for the Botany Department would prove Wilkinson’s downfall in terms of his position as University Architect. He seized the opportunity presented by the Committee’s resolution to design a new two-storey sandstone building, “in a modern version of the perpendicular Gothic, and in perfect harmony with the main University building and the Great Hall,’ as the booklet produced for the official opening of the new Botany School, held on 6 th November 1925, would read.

The Botany Court Lawn viewed from the approach to Science Road on. The Botany building is here largely screened by the Chinese elm, but its detail, including mullioned windows and a turret stair, can be glimpsed. The image is undated, but the completed arch at left of frame suggests it was taken no earlier than 1958. . Courtesy of University of Sydney Archives REF-00077101.

There were many visual benefits from this addition. The new building effectively screened off from Parramatta Road a view of the eastern end of the Macleay Museum that had long been deemed unfortunate by Wilkinson. The booklet produced for the building’s official opening also tells of an attractive garden area introduced on the eastern side of the Botany building, “laid out in a formal manner, in keeping with the main approach to the University, and utilising such features as a lawn, a playing fountain and a small Botanic Garden”. [115]

However attractive the results, the project was dismissed by the University administration as having provided little accommodation at considerable cost,[116] and this assessment came after the event. Wilkinson had made the fundamental error of proceeding with the construction without first formally seeking approval from the Building and Grounds Committee. Had the completed Botany building convincingly demonstrated its practical worth this procedural lapse may have been overlooked, but there was no such defence.

The fact that Wilkinson had, in association with this project, also built the abutments for an archway across Science Road, intended to link the new Botany building with the main Quadrangle, very likely suggested to his superiors that he had lost touch with the priorities attached to the government grant. The arch had been a feature planned since 1890, was included in Wilkinson’s masterplan, and therefore adopted in principle by the Senate. However, at a time when the government funds were all but depleted, and with critical objectives yet unfulfilled, the Science Road archway, as a largely ornamental feature which incidentally housed professorial offices, is likely to have seemed an inappropriate diversion. Simultaneously, Professor Fawsitt’s instincts had been proven correct, and the works designed to increase the teaching accommodation for the Chemistry department had achieved little of what he had hoped for, when the source finally ran dry.[117]

Wilkinson had now lost the confidence of the University administration. It was decided that the Senate should approach the government for a further £50,000, with a proviso that the Government Architect take control of the works aligned to the new grant. However, it was not until April 1928 that Wilkinson was officially informed by the Senate that his appointment as University Architect had related only to the Government funds issued as the post-war grant of £300,000, and since that was expended, the position, too, had lapsed.[118]

When Peter Johnson, a former student of Wilkinson and a later Dean of Architecture at Sydney, wrote in the 1980s about his predecessor’s era, he allowed Wilkinson’s own words, from records in the archives, to tell the story of this controversial interlude. While Wilkinson conceded that, had the work attached to the £300,000 grant been carried out by the Government Works Department, a number of projects that he had failed to deliver would have been completed. However, he also listed what would have been lost without his innovation, resourcefulness and diversion from the narrower scheme:

“no quadrangle, no little quad, no extension of Botany with the opening up of the beautiful north front of the Great Hall, no extension to Zoology, Engineering, the Union or to the Medical School. Added to which the University would not have obtained the stone from the Old Darlinghurst Gaol and the Old Commercial Bank which may be valued at ten thousand pounds, whilst useful buildings valued at thirty to forty thousand pounds would have been destroyed. The advantageous exchange of land between the University and the City Council was also proposed by me …”

Quoted in “Johnson, Peter “Leslie Wilkinson at Sydney University” inLeslie Wilkinson: a practical idealistp. 79.