Thomas Tamara and Nanny Nellola

Thomas Tamara and Nanny Nellola

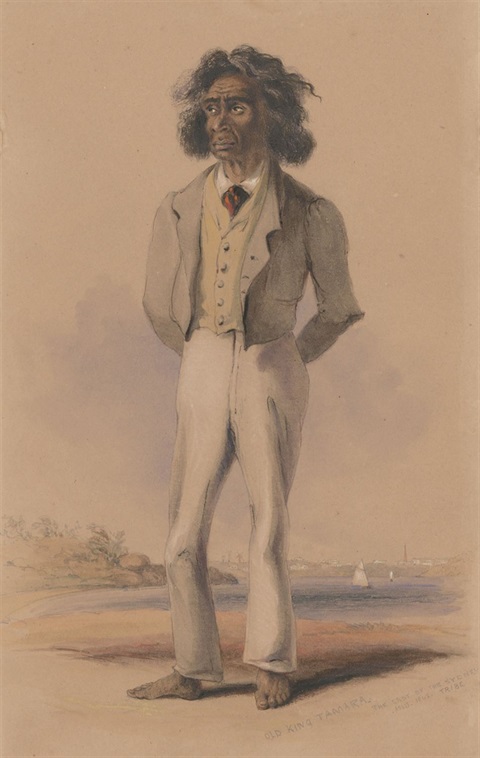

Thomas Tamara and his wife Nanny Nellola were leaders of the 'Sydney tribe'. They straddled two vastly different cultures and navigated a way of life for their group alongside European colonists. Tamara was recognised as a leader of Aboriginal peoples in both coastal Sydney and the Illawarra region.

Image: Watercolour sketch by George French Angas "Old King Tamara. The last of the Sydney Tribe. Aug 15, 1845" held by South Australian Museum, AA8/4/2//3 (not available online). Unfortunately there is no known drawing of Nanny Nellola.

Plaque location

On the waterfront at the end of Ocean Avenue, Double Bay.

View all plaques in Woollahra

Plaque Unveiling Gallery

Colonial settlement of the area now known as Double Bay

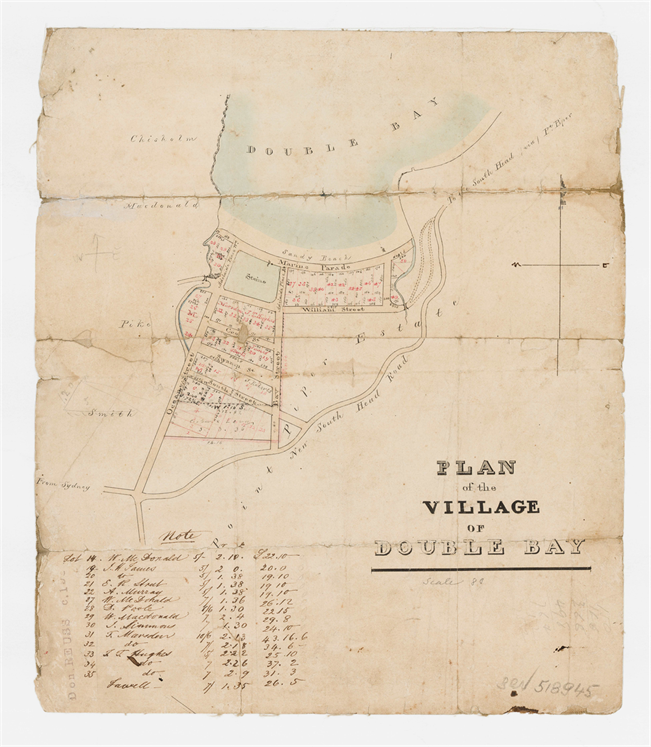

The area behind Double Bay beach had been earmarked by Governor Macquarie in 1821 as a botanic garden. When the plans for the garden did not proceed, the area was instead surveyed in 1834 as the 'Village of Double Bay'.

Plan of the Village of Double Bay, 1834. SLNSW.

European settlement of Double Bay was gradual and by 1845 while there was a small European fishing settlement, the surrounding land was still mostly uncleared of the original vegetations and unoccupied. A Nicholas Caire photograph taken some 30 years after Tamara and Nellola were known to be residing in the area shows that the eastern side of the bay was still heavily timbered with only a few houses visible.

Double Bay 1879, Nicholas Caire, Woollahra Libraries Digital Archive, pf004730.

In 1837, William MacDonald, a successful emancipist, put his land at the Darling Point end of Double Bay up for sale. The promotional sales literature mentioned a 'romantic cave' on the property. This could have been the shelter used by Tamara, Nellola and their group.

Finding records of Aboriginal elders in written colonial sources can be frustrating and difficult. These documents were created by people in power, administrators and artists. Aboriginal people are only evident in written sources if the colonists thought it was important to record them, and given that they had little respect for the local custodians and inhabitants, their presence is often ignored. They appear most often in lists of people to whom blankets were distributed and in the diaries or reminiscences of visitors or early settlers.

Life at Double Bay for Tamara, Nellola and their group

Thomas Tamara was most likely born in the Wollongong area c.1800 and Nanny Nellola in the Botany Bay area at a similar time. There are no records of their births.

The first record of Thomas Tamara in the Sydney area is in the 1820s, in a letter to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald by 'Obed West'. He names some of the 'best known' Aboriginal people of the area and included in his list is 'Tommera', which he admits to spelling phonetically.

A French Catholic missionary and artist, Leopold Verguet, who was visiting Sydney with the Society of Mary, recorded in his diary in June 1845 that Tamara Nellola, and their group of about 20 people were living on Gadigal country in a large sandstone rock shelter at Double Bay beach, most likely situated at the western end (Darling Point end) of the beach.

The translation from Verguet's diary reads:

I found Tamara and his wife peacefully smoking a pipe. I asked Tamara's permission to draw his portrait [...] There under the rock, I made portraits of Tamara, of a woman and of a child. The natives, at first timid kept their distance, then, little by little they gathered around to see my work, and as the picture advanced they burst out laughing in recognising their chief on my paper.[1]

Verguet observed Tamara speaking to one of his fellow missionaries and noted:

The chief made himself understood in a kind of English jargon which the natives learn easily. He showed much good sense in his words; he was not embarrassed like the other natives his eye was lively and sharp, he was conscious of his superiority.

The missionary was keen to know whether Tamara understood the concepts of heaven and hell and believed in an after-life. It is likely that the missionaries did not know that Tamara and Nellola had baptised their daughter, named Gertrude, at St Mary's Cathedral 18 years earlier in 1827.[2]

The practice was promoted by Father John Joseph Therry, who established relations with Aboriginal people around Sydney, during the 1820s, but it became less common from the early 1830s.[3]

After Verguet had finished his portrait, and was preparing to leave, he records that an Aboriginal man arrived and

...had in his hand several wooden spears, several metres long and with three points at one end. I looked at these spears with an air of surprise, which seemed to ask what they were for. Tamara hastened to tell me that they were to harpoon fish; and, in fact, another native soon appeared with a fish in his hand. Having finished my business with Tamara I gave him some bread, some cheese and a cotton cap to thank him for his co-operation. He appeared to me well-satisfied.[4]

Unfortunately, Verguet's portraits of Tamara returned with him to Europe, and have not been seen since.

Port Jackson N.S.W. View in Double Bay S. Side Middle Head in the distance (near sunset),

[from the eastern end of Double Bay beach] by G.E. (George Edwards) Peacock, 1847, SLNSW.

Using the natural resources of Double Bay and the south coast

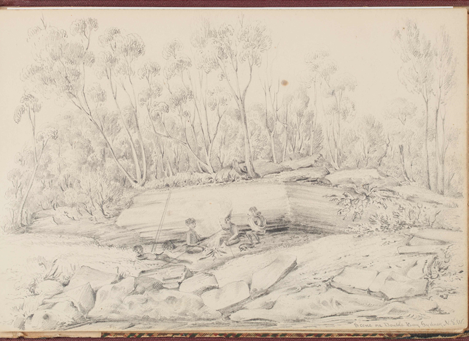

For Tamara's group, fishing was not a hobby but a means of sustenance and trade. There were creeks at either end of the Double Bay beach providing fresh water, a plentiful supply of fish from the harbour, and food from plants and animals from the surrounding bush.[5]

It is thought that the sketch by Henry Campbell dating to about 1842, of a group of five Aboriginal people (including a woman and child) cooking fish at Double Bay, represented some of Tamara's group.[6]

'Scene on Double Bay' by Henry Campbell, 1842, in Sydney Views, SLNSW PXC 291, no. 34.

Tamara, Nellola and others would go to the Sydney markets (located in today's Queen Victoria Building in George Street) to sell excess fish, gum collected from eucalyptus trees and boomerangs. George Angas (who also sketched Tamara in 1845), noted that Tamara was widely recognised 'for his skill in shaping returning boomerangs'.[7]

Like Cora Gooseberry (sometimes known as Karoo) and her group at Camp Cove, the 'Sydney tribe' found a way to co-exist and forge relations with their European neighbours. For example, in January 1845, a fire broke out in bushland surrounding the Cooper family's property at Point Piper. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the group of locals who quickly gathered to fight the blaze were "assisted by a tribe of friendly blacks in the the neighbourhood" and that one Aboriginal man offered to help a convict who was bitten by a snake during the event.[8] The authors of the Woollahra Aboriginal Heritage Study posit that the Aboriginal firefighters were probably from Tamara and Nellola's group and that they were 'deeply entwined in the social and economic life of the colony'.[9] Tamara regularly travelled between Sydney Harbour, Botany Bay and the Illawarra coastal strip where he maintained connections.[10]

He is likely to have travelled by both or on foot. Dr Paul Irish has traced his movements over a 20 year period using documents held in the NSW State Archives which record Tamara (with various spellings of his name) receiving government issued blankets in Wollongong, Parramatta and Sydney.[11]

The wooden fishing boat that Tamara and members of his group used probably came from a donation organised by Sydney lawyer Bob Nichols in 1844. From the late 1830s the Colonial government began to wind back humanitarian assistance to the Aboriginal people and in 1844 stopped the provision of blankets. As a consequence, in June 1844 Nichols organised a meeting to form a committee to raise funds for the purchase of 'a boat, sails etc. and fishing tackle together with a supply of clothes' for the use of Aboriginal people living in Sydney.[12] Irish notes that this was 'almost certainly the group led by ... Thomas Tamara and ... Nanny Nellola' as in 1846 it was recorded that Tamara had ;been presented with a boat, in which he fishes outside the heads and brings his fish to Sydney market'.[13]

In 1846, Tamara, Nellola and about 20 more from their group travelled south by boat 'following the fish'. They were gone from their rock shelter longer than usual, and some European settlers raised the alarm, assuming that they had been 'blown out to sea' from Botany Bay. When the Aboriginal group learned from Mr Brown, a resident of Dapto, that their absence had caused consternation, they sent a messenger back to Sydney to allay those concerns.[14]

Tamara's group returned to Sydney in late 1846 and instead of resuming their state at the western end of Double Bay, they resided on the Wentworth Family estate at Vaucluse. This was most likely because settlement was expanding in Double Bay, whereas the Vaucluse Estate remained relatively untouched until it was sub-divided in the early years of the 20th century.

The last documented record of Tamara and Nellola is from 1846, when they are spent a week at the Benevolent Asylum, a private charity run by the Benevolent Society providing shelter, food and basic medical care.[15] The Asylum was located near where Central Train Station is today, on the corner of Pitt and Devonshire streets. By 1840, 1,058 people were living there.[16] Paul Irish suggests that both Thomas Tamara and Nanny Nellola died in the 1860s.[17]

Sources

[1] Hugh Laracy, 'Leopold Verguet and the Aborigines of Sydney, 1845,' Aboriginal History, vol.4, no.2, 1980, p.181.

[2] Irish, Paul, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, University of NSW Press, 2017, pp. 39-40

[3] Irish, Paul, 'St Mary's Cathedral', in Barani: Sydney's Aboriginal History

[4] Laracy, p.182. p. 11

[5] Woollahra Aboriginal Heritage Study, 2021, p.64.

[6] Irish, 2017, Fig 2.6. and p. 155, Drawing in Sydney Views, SLNSW PXC 291, no. 34. p. 11

[7] Smith, Keith Vincent, 2011, 'Aboriginal life around Port Jackson after 1822', Dictionary of Sydney

[8] 'Incendiarism and its effects', Sydney Morning Herald, 22 Jan 1845, p. 3.

[9] Woollahra Aboriginal Heritage Study, 2021, p. 57 and Irish, p. 49

[10] Irish, 2017, p. 24.

[11] Irish, 2017, figure 1.4 and sources on pp. 154-155.

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 June 1844, p. 3. and The Star and Working Man's Guardian, 8 Jun 1844, p. 2.

[13] Irish, 2017, p. 63 and note 59. p. 111

[14] 'Aborigines', Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April, 1846, p. 2.

[15] Irish, 2017, p. 82 and fig. 1.4.

[16] McCormack, Terri, 2008, 'Benevolent Society and Asylum', Dictionary of Sydney.

[17] Irish, 2017, p. 24 and Woollahra Aboriginal Heritage Study, 2021, p. 56.