Lyndon Raymond Dadswell CMG

Lyndon Raymond Dadswell CMG

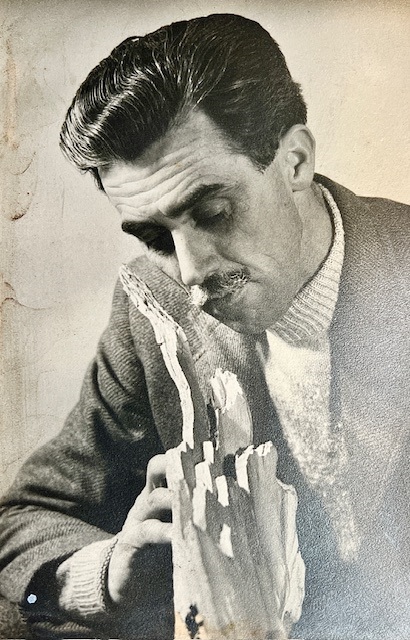

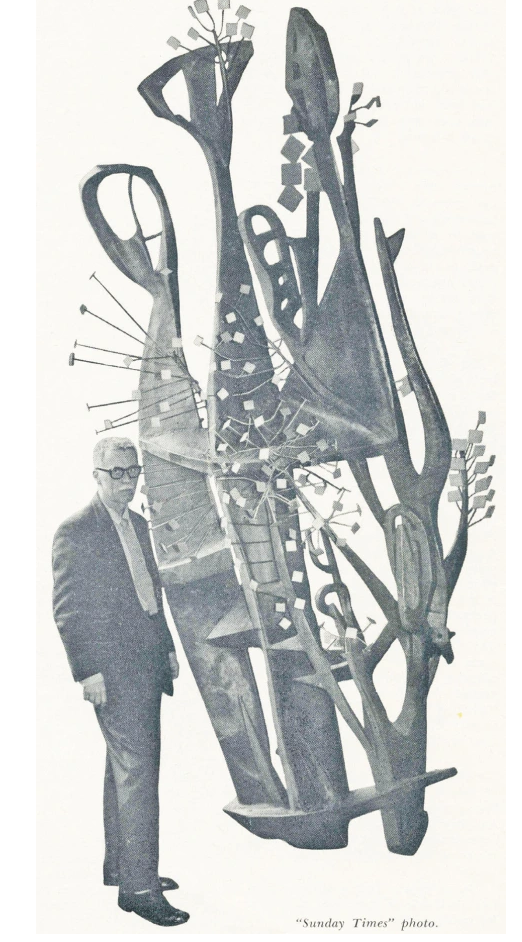

Lyndon Dadswell working on a marquette at home, c. 1953.

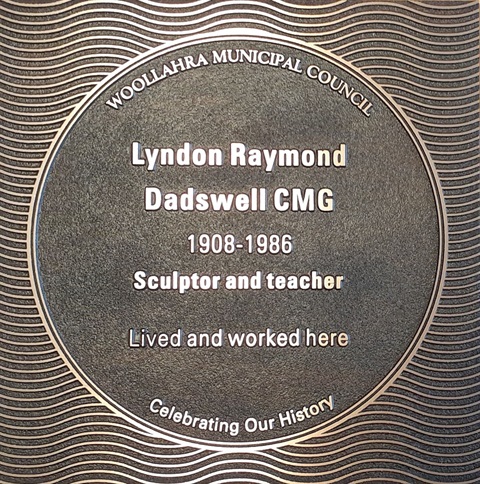

A plaque commemorating Lyndon Dadswell was unveiled on 3 December 2024 by the Deputy Mayor of Woollahra, Clr Sean Carmichael in the presence of Lyndon and Audrey Dadswell's children, Penelope Zylstra and Peter Dadswell. The guest speaker was Dr Deborah Beck OAM, a lecturer, author, artist and archivist from the National Art School. A transcript of her speech is available(PDF, 107KB).

Plaque location

The plaque is located in the footpath outside 21 Trelawney Street, Woollahra.

View all plaques in Woollahra

Plaque Unveiling Gallery

An emerging artist of great prominence

Lyndon Dadswell was born in Stanmore in 1908 and grew up with his sister in North Sydney. After graduating from the prestigious Shore School, he studied drawing at the Sydney Art School (which was renamed the Julian Ashton Art School after the founder's death) in 1924 and 1925. He then moved on to study under renowned British-born sculptor Raynor Hoff at the East Sydney Technical College (which became the National Art School at Darlinghurst) from 1926-1929.

Hoff encouraged Dadswell to leave college in 1929 to assist Paul Montford on a commission for Victoria's memorial to the First World War, the Shrine of Remembrance, in Melbourne. As part of this high-profile project, the 21 year old Dadswell crafted 12 large freestone relief panels in the sanctuary to illustrate the work of the men and women in the Australian armed services.

While the project occupied him for the next four years, he also found time to enter the Wynne prize, which is awarded annually for 'the best landscape painting of Australian scenery in oils or watercolours or for the best example of figure sculpture by Australian artists'. Dadswell won the prize in 1933 for his figurative sculpture 'Youth', thus becoming only the third sculptor to be awarded the prize since it commenced in 1897.

Three of the twelve commemorative panels in the frieze designed by Dadswell for the sanctuary. Photo reproduced courtesy of the Shrine of Remembrance.

Each panel in the frieze was 2.2 metres wide and 2.6 metres high. Photo reproduced courtesy of the Shrine of Remembrance.

Serving with a gun and a chisel: World War II

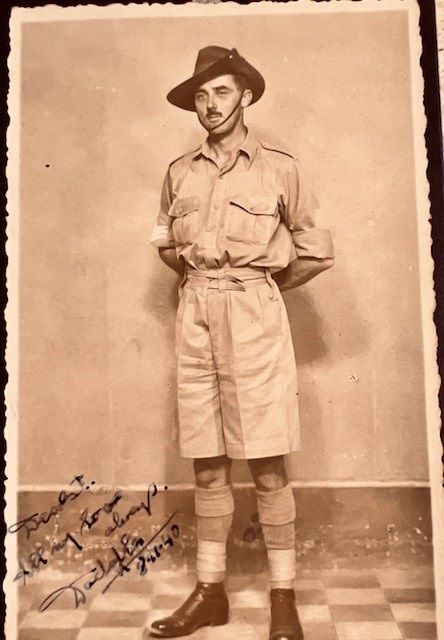

In response to the outbreak of World War II, Dadswell enlisted in the 2nd Division of the Australian Imperial Forces on 29 April 1940 (service no. NX13548). He embarked for the Middle East on 30 August 1940 and fought in Greece, Libya and Syria. On 22 June 1941, he sustained gunshot wounds to his head and left leg in Syria. After recuperating in Cairo, he was promoted to lieutenant and commissioned as an official war artist in September 1941.

Lyndon Dadswell in uniform, 1940.

Dadswell was the first sculptor to be appointed as an official Australian war artist. Stationed in Cairo, he produced works based on his experience of war time service in the Middle East. Dadswell's work from this period shows artistic and philosophical shifts. His sculptures transition from the purely figurative and naturalistic, to modernist abstraction. On a personal level, his work shows that he 'transcended his personal sense of the futility of war, to create sculptures that expressed great admiration for the determination and courage of the soldiers he had fought alongside.'[1]

A number of his sculptures were included in the touring exhibitions of works by Australian war artists in 1943-44. In August 1942, Dadswell returned to Australia and resigned from his commission as official war artist later that year.

Dadswell in Cairo with his sculpture 'Soldier in summer dress', 1941.

Teaching and artistic career

In 1937, an impoverished Dadswell returned to Sydney from London, where he had accepted a scholarship to study at the Royal Academy School and toured the art capitals of Europe on a cheap bicycle, to take up a teaching position in modelling and sculpture at East Sydney Technical College.

As a teacher, Dadswell nurtured and inspired a generation of Australian sculptors, among them Robert Klippel and Tom Bass. While he shared his technical skills and imparted his wisdom, probably his greatest gift to his students was to make them open to experimentation, and confident to find and follow their own path. Artist Peter Powditch said: 'Lyndon Dadswell taught me to see. John Olsen taught me what to see.'[2]

Painter, sculptor and Holocaust survivor Olga Horak, who battled the unwanted emergence of dark imagery in her art, credited him with freeing her. "He understood my memories and encouraged me to see and model a human figure for its forms, not for the past trauma. He taught us respect for material and forms."[3]

Dadswell was promoted to the head of Fine Arts in 1966. During that year, he also travelled to Canberra weekly to teach sculpture at ANU.[4] After 31 years he retired from teaching in 1968, but not from his artistic practice or the promotion of sculpture. Dadswell supported fellow sculptors and fostered public appreciation of sculpture as a medium. He was actively involved in organisations such as the Society of Sculptors, and exhibited in the inaugural Australian Academy of Art exhibition in 1938. Sculpture has been described as 'the Cinderella of the Australian Arts'[5] and Dadswell did all he could to elevate its status.

Dadswell was active as a sculptor for nearly 50 years, and never tired of trying new materials and techniques. He faced frailty with further inventiveness, exploring new materials such as sheet metal and laminated paper on skeleton wire. His imagination and purpose allowed him to fulfil an abiding creative impulse.

A retrospective exhibition of Dadswell's work was held at the AGNSW in 1978. In the same year, he was awarded the Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in recognition of his services to sculpture. The following year, Australian-American modernist sculptor Margel Hinder observed: 'there is hardly a sculptor in Sydney who is not indebted to Lyndon in some measure'.[6]

Lyndon Dadswell, 'Self-portrait in Plus Fours', c. 1939 (cast 2003), cast bronze 89.0 x 33.0 x 25.0 (overall, irregular), National Portrait Gallery Collection. Image reproduced with permission from NPG.

Sculpture commissions

Dadswell won several commissions for civic buildings. In addition to the 12 panels which he conceived and create for the inner sanctuary of the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne at the age of just 21 years, he also created sculptures for the Maritime Services Board building, Sydney (1952); Commonwealth banks in Hobart and Sydney (1954) and Perth (1960); the Newcastle War Memorial Cultural Centre (1957); Adelaide's Rundle Mall (1959); the R. G. Menzies Library, Australian National University (1964, which he said was his favourite work); the Sydney Jewish Museum, Maccabean Hall (1965); and the Campbell Park defence establishment, Canberra ('Growth, Tree of Life', 1977).[7]

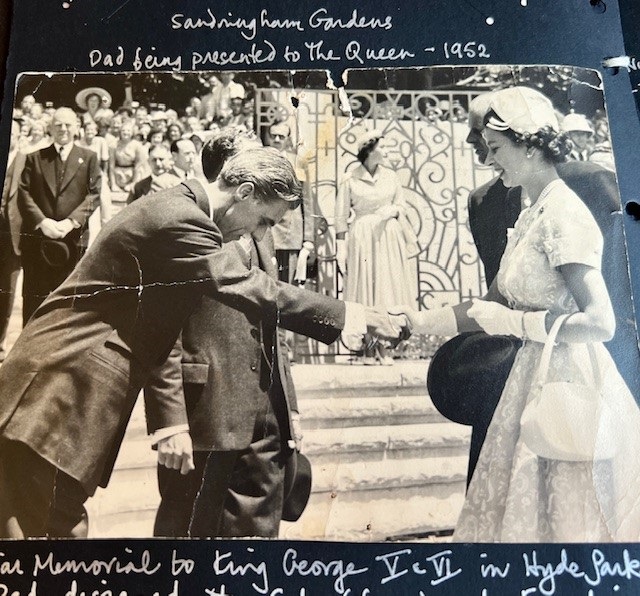

In 1954, Dadswell worked with architect Henry Epstein to create a gated, terraced garden and fountain as a joint memorial to King George V and King George VI after the sudden passing of King George VI in 1952. Dadswell designed the bronze gates, which include the crests and heraldic motifs of King George V and King George VI, and the abstract mosaic at the base of the fountain. The memorial, known as Sandringham Gardens, is situation in Hyde Park, Sydney, and was opened by Queen Elizabeth II when she visited Australia in 1954.

Lyndon Dadswell being presented to Queen Elizabeth II in front of the gates that he designed for Sandringham Gardens, 1954 (not 1952 as written in the family album).

Almost a decade later, Epstein and Dadswell collaborated again when they worked on an extension to the Maccabean Hall for the Sydney Jewish Community. Epstein's brutalist design was complimented by Dadswell's abstracted seven-branch Menorah, which was carved into the façade of the building facing Darlinghurst Road.

Extension to the Jewish Maccabean Hall featuring Dadswell's sculpture, 1965. Photograph: Peter Collie, 2017. Sydney Jewish Museum Collection.

Not everyone shared Dadswell's artistic vision or appreciated his creativity. In 1960, the reception for Dadswell's commissioned sculpture, 'Wildflower State', was somewhat bemused and lukewarm when it was installed on the side of Perth's Commonwealth Bank building. When the building was demolished nearly three decades later, the artwork was purchased from a scrap metal merchant by a Perth welder and proprietor of P.G.N. Fabrications, Paul Nield. He leased the three metre high modernist sculpture made of oxy-welded and beaten copper and baked enamel squares to Macquarie University for display in its Sydney sculpture garden. Dadswell admitted that the bold artwork "does not pretend to imitate nature, but does seek to provoke thought - to hold attention." In August 2022 the sculpture was auctioned by Lloyd's, and purchased by a private individual from Western Australia who, in his determination to bring it back to its home state, bid $81,000, thereby setting a new record for Dadswell's work.[8]

Dadswell with his sculpture 'Wildflower State', 1960.

Local connections

Lyndon Dadswell became a resident of Woollahra in the 1940s. In December 1939, he married Audrey Margaret Herbert, and the couple settled in Potts Point before Lyndon's enlistment in the 2nd Australian Imperial Forces parted them for several years during the war.

Following Lyndon's discharge in 1945, he and Audrey settled at No 5 Manningham, 21 Trelawney Street, Woollahra. This became their family home, shared with their two children, Penelope and Peter, and shared with sculpture, as for a time it doubled as Lyndon's studio.

During his years as a Woollahra resident, Lyndon participated several times in exhibitions mounted by the Woollahra Arts Centre, then operated by Dora Sweetapple from Woollahra Council's property St Brigid's, which now houses Council's Art Gallery. An exhibition in 1952 featured the finished artwork of sculptors such as Dadswell, Robert Klippel, Tom Bass and Margo Lewers while also demonstrating the phases in the development of a sculptural work, from concept to completion. An 'art critic' described it as 'thoroughly, if not aggressively modern'.[9] [10]

In 1954, Dadswell's art was again part of a Woollahra Arts Centre exhibition, the 'Festival of Talent', which was mounted to coincide with the visit of Queen Elizabeth II, and aimed to showcase 'all aspects of art produced in the municipality'.[11]

By 1948, Lyndon had found a suitable studio space at an easy distance from Manningham. He set up his studio in a converted stable behind the house of artist and friend Douglas Dundas and his wife Dorothy. They leased their property at 302 Jersey Road from the Anglican Church, which owned the Edgecliff glebe. The place where Lyndon's studio stood is now part of Anglicare's Goodwin Village, which was built in the 1960s as part of the large-scale redevelopment of the glebe that was precipitated by the coming of the Eastern Suburbs Railway and the Edgecliff train station.

In 1963, as they watched Edgecliff change, the Dadswells purchased a terrace house in Goodhope Street and moved to Paddington. They felt at home in a suburb that attracted 'musicians, poets, artists, journalists, anarchists and free thinkers', as design historian Professor McNeil has written.

Lyndon Dadswell died in Sydney on 7 November 1986, aged 78. He was survived by his wife Audrey, and their children Penelope and Peter.

Manningham, the house where the Dadswells lived at Trelawney Street, Woollahra.

Awards

1930 Wynne Prize for 'Youth'

1935 Royal Academy School in London - scholarship

1943 Official War Artist, Australia War Memorial

1955 Newcastle Memorial Prize

1967 International Co-operation Art Award

1967 Britannica Australia Award for Art

1878 Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) for 'distinguished service to sculpture'.

Lyndon Dadswell at an exhibition opening, c. 1960.

Sources

[1] 'Lieutenant Lyndon Raymond Dadswell', Australian War Memorial website, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P65045, accessed 27 November 2024.

[2] "2017 National Art School Fellowships: Foley Powditch, Storrier", Art Almanac, 22 May 2017, https://www.art-almanac.com.au/2017-national-art-school-fellowships/, accessed 27 November 2024

[3] Vytrhlik, Jana, “The birds were hungry too”, https://sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/news/the-art-of-holocaust-survivor-olga-horak/ accessed 27 November, 2024.

[4] "The great Dadswell mystery", The Canberra Times, 17 February 1966, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/105887288?searchTerm=The%20great%20Dadswell%20mystery, p. 3.

[5] Johnston, George, “Sculpture is the breadline of Australian art”, The Sun, 13 September 1950, p. 23.

[6] “Lyndon Dadswell, CMG”, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.portrait.gov.au/people/lyndon-dadswell-1908, accessed 27 November 2024.

[7] Deborah Edwards, 'Dadswell, Lyndon Raymond (1908–1986)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dadswell-lyndon-raymond-12389/text22267, published first in hardcopy 2007, accessed online 27 November 2024.

[8] Grant, Steve, ‘Blooming Marvellous’, Perth Interactive Voice, 8 September 2022, https://perthvoiceinteractive.com/2022/09/08/blooming-marvellous/ accessed 27 November 2024.

[9] Gleeson, James, "Layman can see sculptures in the making", The Sun, 5 November 1952, p.15.

[10] “Exhibition by sculptors", The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 1952, p.2.

[11] "Woollahra art display", The Daily Telegraph, 8 February 1954, p. 15.